Seal gland design is an important aspect of effective spring-energized PTFE seals and is also the source of most leaks. Such seals can only perform as well as the seal gland supporting them, and even a small geometry error can lead to issues with extrusion, rapid wear, low contact stress, and spiral leakage.

This blog post reviews what makes PTFE spring-energized seals different from other sealing solutions, and then discusses key aspects of gland design, including the anatomy of a basic spring-energized seal and design aspects of geometry and surface finish that have the greatest impact on seal reliability.

Anatomy of a Spring-Energized Seal

A short review of spring-energized seals is in order.

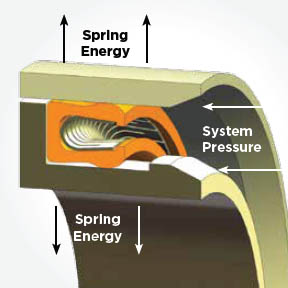

The gland is the machined groove in the metal hardware where the seal sits. In the diagram, you can see the E-gap, or extrusion gap. This is a small clearing between the moving and stationary metal parts of the seal. This gap must be kept tight to prevent the seal from extruding or flowing into it under pressure.

The seal jacket is the U-shaped outer body, which, in PTFE spring-energized seals, is manufactured from PTFE. It provides the main sealing interface against the hardware, and the lips of the jack are the points that actually touch the mating surface.

The spring energizer is contained within the jacket, and it provides constant pressure against the jacket lips and provides pressure outward against the gland walls. This pressure, or sealing force, is maintained by the spring-energizer within the jacket and exists even when there is low to no system pressure. As system pressure increases, the jacket enters the U-cup and further augments the spring’s force and the sealing force.

Practical Seal Gland Design Geometry

PTFE is not flexible like elastomers, and that must be taken into account when specifying the gland geometry. First, proper gland width provides the seal with enough clearance to float, and the gland depth strictly controls the interference, and both are critical for providing sufficient axial and radial freedom instead of just simply squeezing the seal into place.

When the design creates over-compression, the seal will not be able to flex as it should. This leads to increased friction, accelerated jacket wear, and a potential locked condition where the spring cannot compensate for shaft misalignment. Under-compression brings its own set of problems because it will not be able to fully utilize the spring energy. Leakage at low pressures and a delayed response during pressure spikes severely impact the performance of the seal.

The goal with the design then becomes the achievement of a uniform load distribution that can conform to surface irregularities and maintain the integrity of the seal.

Seal Gland Design: Corner Radii and Lead-In Geometry

PTFE is softer than steel. If you try to shove this plastic seal into a metal bore that has a sharp 90° corner, that corner acts like a knife. It will slice a layer off your seal before the machine even turns on. This can lead to micro-damage that will later present itself as problematic leaks.

Sharp edges are one of the main causes of damage during PTFE seal installation, and this differs significantly from elastomeric seals. PTFE is stiffer, which makes it more likely to suffer a cut from insertion into a metal bore at a 90° angle. The solution is a shallow lead-in chamfer or on-ramp that is around 15° to 20°, and longer than the seal itself. The length is necessary to ensure the seal is fully compressed before it enters the main bore. In addition, the ramp corners must be rounded, and no sharp edges are allowed.

Seal Gland Design: Surface Finish and Hardware Interaction

Because these seals are constantly rubbing against metal, the surface finish of the metal is of utmost importance. If the surface is too rough, it will abrade the seal and lead directly to leakage. On the other hand, if the surface is too smooth (e.g., mirror polish), it will not be able to hold, and the seal will wipe the sealing surface dry. In addition, because PTFE is self-lubricating and forms a transfer film on the sealing surface, the surface cannot be so smooth that the transfer film does not stick. 2 RMS to 16 RMS, depending on what your application is.

For gases and liquids at cryogenic temperatures, you want a smoother finish with an RMS between 2 and 4. For gases at non-cryogenic temperatures, the recommended surface finish is between 6 and 12 RMS. For liquids, a surface finish between 8 and 16 RMS is sufficient.

In addition, it is important to specify a plunge-ground finish (0° lead) to prevent spiral tool marks from acting as a screw pump that leaks fluid regardless of seal tightness.

Seal Gland Design: Squeeze, Clearance, and Extrusion Gap Control

Under extremely high pressures, the behavior of PTFE is significantly different from that of elastomers. At extremely high pressures, PTFE is more likely to flow like a liquid to an area of lower pressure. There will always be a small gap between your piston and cylinder wall to prevent them from grinding against each other. This small gap is known as the extrusion gap, or E-gap. If the gap is too large, the pressure will push the heel of the seal into the gap, shredding the seal. This is where careful specifications come in: when specifying the diameter, include a small enough tolerance to ensure that the gap remains small (e.g., smaller than a human hair) even when the parts move.

Conclusion

Seal gland design for PTFE spring-energized seals is a little different from elastomeric seals and involves more focus on aspects such as geometry, lead-in geometry, surface finish, and extrusion gap control.

If you need help with a PTFE spring-energized seal, our engineers at Advanced EMC are here and ready to help. Contact us today!