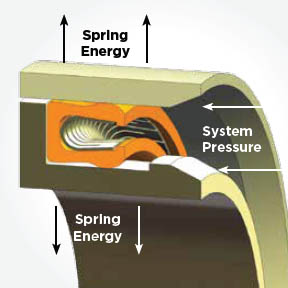

PTFE rotary shaft seals behave very differently from their elastomeric counterparts. Because one of their primary mechanisms is transfer film, they have different requirements related to the mating surface to achieve a successful solution. This blog post looks at three key factors that impact the performance of PTFE rotary shaft seals: surface finish, hardness, and coating.

Surface Finish

For PTFE rotary shaft seals, surface finish is extremely important. To achieve the least possible friction with a PTFE seal, the mating surface needs a specific texture. The mating surface must be rough enough to abrade a microscopic amount of PTFE to form a transfer film during the break-in period. This transfer film achieves a PTFE-on-PTFE effect, resulting in extremely low friction.

If the surface finish is too smooth, on the order of <2µm Ra, the transfer film will not adhere. To make matters worse, the seal lip will hydroplane, experience stick-slip friction, and generate significant heat that can char the lip.The surface finish can be too rough, as well. If the surface is > 4µm Ra, the shaft will act like a file, abrading the seal lip faster than the transfer film can form. This damages the seal itself and causes leakage.And while Ra is key, Rs (Skewness) is also important. The goal is to achieve negative skew so the surface has plateaus and valleys rather than sharp peaks that can slice the seal.

In addition, if the shaft is finished using a standard turning process, it may look perfect, but result in mysterious leaks. During standard turning, microscopic helical grooves are left in the shaft material. The grooves are like the threads of a screw, and during rotation they can pump oil under the seal through this micropump effect. The industry standard for PTFE is a plunge-ground finish, which ensures that marks from turning and grinding are circumferential, eliminating the pumping effect.

Hardness

PTFE is a soft material that normally would not damage a metal surface, but virgin PTFE is rarely used for a rotary shaft seal. In such cases, PTFE is filled with glass fibers, bronze, carbon, or graphite — all abrasive fillers — to improve structural integrity and sealing performance. If the shaft is softer than these fillers, the seal will wear a groove into the shaft and leak. To prevent this, experts recommend a mating surface with a hardness of 55-65 HRC (Rockwell C).

Surface Coatings

Surface coatings on the mating surface are often used to achieve the required hardness or to repair a worn shaft, but this can lead to issues if not done correctly. PTFE is an excellent thermal insulator, and PTFE rotary shaft seals depend on the shaft to conduct away the heat generated by friction. Some ceramic coatings are also thermal insulators, and when used they can trap heat at the seal interface. This can lead to a rise in temperature that softens the PTFE and leads to seal failure.

For such reasons, many engineers will use hard chrome as the shaft coating because it is both hard and thermally conductive. Another option is DLC (Diamond-Like Carbon), which has sufficient hardness to prevent grooving and an extremely low coefficient of friction that significantly reduces heat buildup at the lip of the PTFE seal.

Conclusion

Because PTFE rotary shaft seals are fundamentally different from their elastomeric counterparts, they have different requirements for the mating surface. For a successful sealing solution, engineers must consider the surface finish, hardness, and coatings or run the risk of leaks.

If you need a dynamic sealing solution, consider PTFE rotary shaft seals. Contact us today to learn more about your options and how Advanced EMC can support you design needs.