Startup and running friction can vary based on several different factors, and in this article we focus on what they are, why their values differ, and typical coefficients, as well as a detailed look at why these differences occur. It ends with a discussion of what impact startup and running friction have on bearing design.

Startup and Running Friction

Polymer bearings tend to exhibit higher breakaway (startup) friction than steady-state running friction due to factors such as static adhesion, microasperity interlocking, and transfer-film formation dynamics.

The startup friction coefficient µₛ is measured at the onset of motion and represents static friction. The term “startup” does not refer solely to time zero, however. It represents the peak friction force or torque required to break the bearing free after a period of rest. Startup friction is actually the regime of dry contact when the polymer surface is still unconditioned. Unconditioned means that the transfer film on the counterface is incomplete or patchy

The running friction coefficient µₖ represents a kinetic or dynamic measure of friction. It takes place when steady sliding motion is established and is represented by. Running friction relates to the frictional resistance that exists when two surfaces are in motion, steadily sliding against each other.

Running friction applies after the initial breakaway event has occurred and the system has moved past issues such as static adhesion and micro-locking. As a result, the coefficient of running friction is typically lower and more stable than startup friction, especially for materials such as PTFE and UHMW-PE.

Why Startup and Running Friction Can Differ in a Polymer

There are some key factors that differentiate startup friction from running friction in polymers. For example, at rest, there is adhesion and junction growth. Polymer chains can increase the real contact load at under load rest (creep/relaxation), thereby increasing µₛ.In addition, at startup, there will be surface roughness and plowing. The roughness increases issues with mechanical interlocking and plowing. These two effects also raise the starting friction value.

In running friction conditions, materials like PTFE form a transfer film that reduces the effect of asperities and surface roughness, which reduces running friction. There is, however, a risk of stick-slip. This phenomenon is more likely to occur when the stiffness of the system is low, the speed is low, and the µₛ / µₖ ratio is high.

Typical Coefficients of Friction

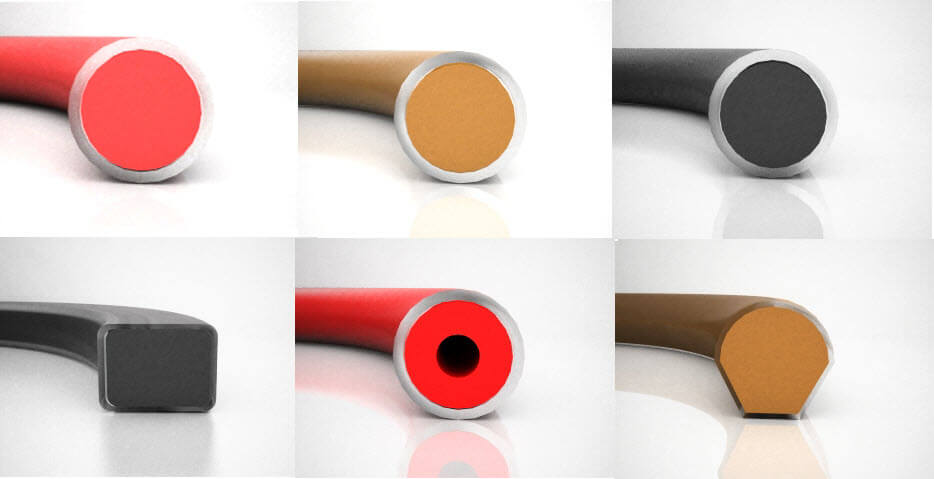

The values below represent commonly used engineering polymers and are typical dry sliding vs steel values. These values can vary with pressure, speed, temperature, finish, fillers, and test method.

- PTFE (virgin)

- Startup friction (µₛ): ~0.05–0.10, often nearly identical to running friction

- Running friction (µₖ): ~0.05–0.10

- Minimal difference between startup and running friction

- PEEK (unfilled)

- Startup friction (µₛ): ~0.20

- Running friction (µₖ): ~0.25

- Exhibits a noticeable increase from startup to running friction

- UHMW-PE

- Startup friction (µₛ): ~0.15–0.20

- Running friction (µₖ): ~0.10–0.20

- Running friction can be equal to or lower than startup friction

- Nylon 66 (PA66)

- Startup friction (µₛ): ~0.20 (against steel)

- Running friction (µₖ): ~0.15–0.25 (typical)

- Moderate variability depending on surface finish and condition

What Is Behind the Difference Between Startup and Running Friction

Several factors account for the difference between startup and running friction. Pressure and dwell time, for example, mean that higher loads and long dwell times increase the real contact area and have the potential to raise µₛ. For speed, higher speeds can actually reduce friction after the polymer transfer film stabilizes, but can also raise heat generation.

Temperatures are known to impact polymer modulus and creep, which can shift both µₛ and µₖ and alter the risk of stick-slip. In addition, the counterface material and hardness will affect the adhesion and transfer film, which is why it is important that the frictional coefficient used in design calculations represents the friction against the counterface material (e.g., PTFE vs steel, PEEK vs aluminum).

Note that PTFE-filled PEEK, MoS₂-filled nylon, and glass/bronze-filled PTFE shift friction and wear differently, often lowering friction but sometimes increasing counterface wear.

Surface finish also has a significant impact. If the surface finish is too rough, plowing will occur, increasing both friction and wear. On the other hand, if the surface finish is too smooth it can increase adhesion issues.

Impact on Bearing Design

Startup and running friction impact material selection, clearance, and surface finish in bearing design. Startup friction is dominated by static friction and adhesion at rest. This fact significantly impacts breakaway torque and can be a limiting factor in low-speed, intermittent, or precision motion systems. In such systems, stick-slip, noise, and control instability are unacceptable.

Running friction, on the other hand, is governed by dynamic friction. Once motion is established, it controls steady-state heat generation, wear rate, and long-term dimensional stability. It directly influences PV limits and service life.

Because many polymers exhibit higher startup friction than running friction, engineers need to balance low breakaway forces with acceptable operating temperatures and wear. This is usually accomplished through the use of self-lubricating materials, fillers, or surface texturing to manage both regimes. A successful polymer bearing design accounts for the full friction lifecycle, ensuring reliable motion at startup without sacrificing durability during continuous operation.

Conclusion

Startup and running friction have a significant impact on bearing design, as well as factors such as material fillers, pressure, temperature, and counterface material. If you are looking for a polymer bearing solution, contact the experts at Advanced EMC. Our team of bearing specialists can help you find the best bearing material for your design and can help you select the optimal material from our range of bearing-grade polymers.